The Psychosomatic Family in Child Psychiatry

Salvador Minuchin (M.D.) and H Charles Fishman (M.D.)

Abstract

This paper contrasts the individual and contextual approaches to the psychiatric treatment of psychosomatic diseases of children. In contrasting the contextualisation of the ‘self’, the authors discuss an expanded ‘self’ inherent in the family-oriented approach. An investigation involving psychosomatic and normal diabetic children and their families demonstrates this concept. The authors present a case of an asthmatic child and discuss and contrast approaches to the area of diagnosis, etiology, maintenance of symptoms, ideas of change and treatment.

Text

In the first issue of the Journal of Psychosomatic Medicine which appeared in 1939 the editors proposed that the object of this ‘new field’ was to “study in their interrelation the psychological and physiology aspect of all normal and abnormal bodily functions and then to integrate somatic therapy and psychotherapy.”[ref]J. of Psychosomatic Medicine, 1 (1939): 1[/ref] Over the next forty years investigators worked diligently in numerous areas following lines of investigation begun by such disparate thinkers as Cannon, Selye, Freud, Alexander, Wolf and Miller. Yet, for all the effort expended over these years, all the careful work and brilliant hypotheses, psychosomatic medicine, to quote George Engel, “has failed to deliver much more than platitudes and largely untestable hypothesis… increased understanding has not been reflected by more effective methods of therapy.”[ref]G. L. Engel, Training in psychosomatic research, Advances in Psychosomatic Medicine, 5 (1967): 16.[/ref]

It is our premise that psychosomatic psychiatry as a field has been hampered by two dichotomies – the mind/body duality and the individual/context schism. Current thought has, at least for the time being, laid the mind/body discontinuity to rest; the individual/context split in which the person and his social field are viewed as discontinuous, however, is currently controversial. It accounts for two contrasting approaches to psychosomatic diseases in children – the individual psychodynamic and the family-contextual approaches. In these pages we will attempt to distinguish these two approaches and to elucidate differences in conceptualizations and treatment of a case involving a child with asthma.

A child psychiatrist studies the child in the context of the family. He explores the significance of the infant-mother relationship in the later development of the child and is cognizant of the influence of the social environment on the unfolding of the child’s potential. In general, he is aware of the dependency of the child, a developing psychosocio-biological organism in a social field which is undergoing developmental transformations as well. Child psychiatrists, by the nature of their field of studies, are explorers of context.

Adult psychiatrists discover children in the retrospective memories of adults in trouble. In the optimistic theorizing of the 19th century, the goal of psychotherapy became directed at enabling adult patients to overcome the disorganizing influences of their development as child. In this endeavour, adult psychiatrists and their adult patients relegating the patient’s social context to the status of a mere backdrop against which the real drama was played: that of the adult struggling against the encroaching child inside of him/her. By the very nature of their field of study, adult psychiatrists have construed the essential characteristics of man as unrelated to his context.

The specialty of adult psychiatry developed, historically, decades before child psychiatry, and lent to the new field a paradigm that carried with it an implicit separation between man and context. It is an artefact of the historical development of child psychiatry as a sub-specialty of adult psychiatry that this child-context dualism distorted the observation of the inherent child-context continuity which, in our opinion, should be the focus of this field of child psychiatry.

It is our view that the paucity of positive results in the field of childhood psychosomatics springs from the dichotomies that we have discussed. As the mind/body split did to previous generations, so the child/context separation has blurred our vision of the continuity of the child’s inner and outer space.

Grinker expresses the need to synthesize this discontinuity when he says “our assumption that the human organism is part oE and in equilibrium with its environment…bring(s) us to the realization that a large aspect of psychosomatic organization has been neglected by most observers… The focus has been on unidirectional, linear causal changes… (but) the actual functioning of the organism cannot be understood except by a study of its translational processes as occurring in a total field.”[ref]Roy R. Grinker, Psychosomatic Research, New York: W. W. Norton & Co, 1953. p. 153.[/ref]

Using this new paradigm, the child-in-context, to look at children, we find ourselves with a different field of observation. The family—oriented child psychiatrist studies the family in which the child is imbedded and speaks of the “psychosomatic family”. This term points to the discrepancy in the two approaches and is obviously incorrect to an individually-oriented chid psychiatrist. For him, “psychosomatic” can describe only the identified patient not the behavior of the family. The term “psychosomatic family” reflects the dilemma of the family-oriented child psychiatrist who inheritied a vocabulary in which words reflect the description of individuals. If we use, instead of psychosomatic, the term “psychosomatogenic” family, this would continue to place us in a linear framework, one which attributes causality to family and therefore, makes the child the victim. However, a contextually-oriented child psychiatrist wants to describe a different phenomenon, one in which verbs are more useful than nouns. Rather than describing personality or historical antecedents, the family-oriented child psychiatrist attempts to describe the interpersonal transactions between family members. More specifically, he scans the system and describes those transactions that organize the behavior of family members in dysfunctional patterns which lead to the manifestation of psychosomatic symptoms in a child. This approach assumes an epistemology that conceptualises a harmonious integration of the child’s inner and outer context. The family-oriented child psychiatrist sees the self as existing both inside and outside of the person: in this conceptualization, the ‘self’ is expanded to include feedback from significant people in the person’s social context. This notion of self is markedly different from the individually-oriented approach with follows the intuitively evident observation that since the individual’s body is surrounded by integument, his self must be similarly discontinuous from his context.

Let us clarify the family-oriented practitioner’s concept of ‘self’ with a metaphor used by Gregory Bateson.[ref]Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind, New York: Ballentine Books, 1972. p. 318.[/ref] He describes a blind man walking with a cane down a street and presents the hypothetical questions: Does the self of the blind man end at his hand holding the cane? Does it include the cane up to its end, but before it touches the sidewalk? Or, could we consider that it ends in the middle of the cane? This is clearly a different way of conceptualizing the individual so that the self is expanded to include the feedback from the man’s context. The self of the child at a given moment then would be the result of his previous experience plus the demand characteristics of his social context. Both the individual and system paradigms concur on the idea that the child develops his/her sense of self as a result of interacting with objects and significant others in a more or less constant environment. The child-in-context paradigm goes beyond the concept of the constraint of self by historical determinants to include the transactions with significant others in the present. These transactions represent an extra-corporeal part of the self. The complex repertory of thoughts, feelings and behavior, more or less, formulated or felt, represent the child’s multifaceted self. The child’s significant context calls forth certain of these characteristics while others become unattended and psychologically unimportant. Therefore, the child’s social ecology makes prominant those aspects of child’s personality that are appropriate to the context. This concept would then encompass the self in its historical continuity and as a changeable and responding entity.

Traditionally child psychiatrists have focused on pathological characteristics manifested by the sick child, neglecting the rich repertories of personality traits which were learned along with the currently observed dysfunctional patterns. The child has a repertory of potential coping behaviors that remain quiescent as a result of the demand characteristics of his social field. For example, consider the asthmatic child who wheezes at home on weekends but who can ride his bike 6 miles with friends. Or the diabetic child who develops ketoacidosis while intervening in this parents conflict but who controls his metabolism while visiting his grandparents.

The child in turn affects his context: a figure/ground shift occurs as a result of the child’s behavior so that significant people will interact with the child in ways induced, at least in part, by the child’s response. But, of course, the behavior of the child was induced at the same time by the significant people. It is a circular process. In fact, it is the inherent circularity of this process of mutual affecting and reinforcing which maintains the fixed behavioral pattern in people who are viewed in this approach as immanently changeable.

Since it is our premise that the demand characteristics of the family context in which psychosomatic children live play a major role in maintaining them as symptomatic it is at least as important to change the child’s social system as it is to modify and expand the repertory with which the child responds to stress. We are not, however, advocating scotomae of the biological or psychological aspects of psychosomatic disease. Certainly, it has been well documented that the control of the contradictions of the bronchioli in the asthmatic child can be accomplished on many levels: at the psychological/physiological level when the child recognises an aura and manages to control the asthmatic attack by introducing voluntary control on his neurovegetative system at by transforming the patterns of mutual regulation between family members.

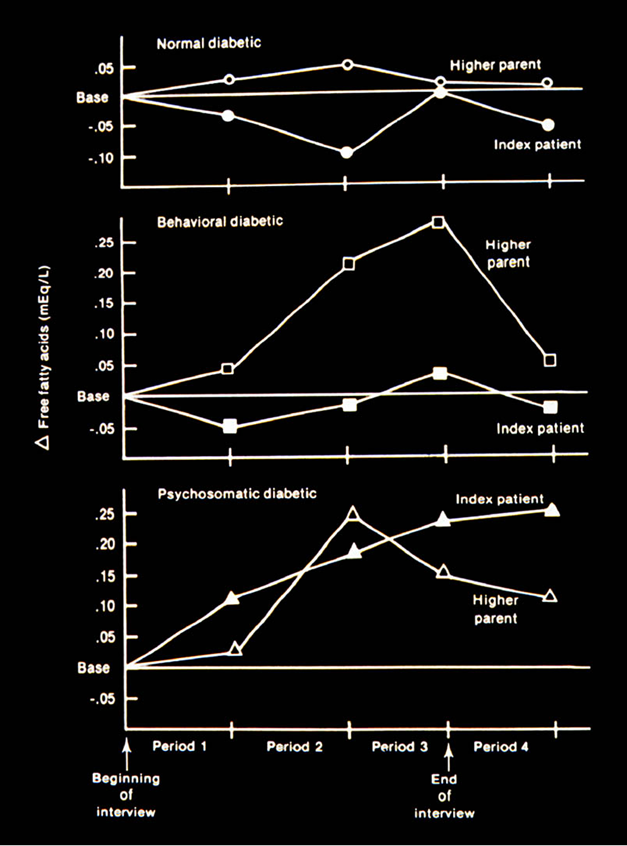

The continuity of the physiology of the child, his psychological constructs, and his extra-corporeal self were demonstrated empirically in a group of psychosomatic youngsters. These children appeared to be suffering from psychosomatically induced exacerbations of their diabetes mellitus. The following experiment, explained in detail elsewhere,[ref]S. Minuchin, B. L. Rosman, L. Baker, Psychosomatic Families: Nervosa in Context, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978, p.47.[/ref] was performed. The children along with their parents were seen for a stress interview. During this interview, the child and both parents had intravenous needles through which aliquots of blood were withdrawn at regular intervals. The interview was divided into four parts. During the first two parts, the child was outside the room observing his parents through a one-way mirror. Following a baseline period in which the parents spoke about neutral topics with one of the investigators, the parents were asked in Period I to discuss problems in the family. In Period II, the interviewer entered and exacerbated stress by siding with one parent against the other. During the third period, the child came into the room and the interviewer left. In this part a characteristic transactional pattern is seen in psychosomatic families. The parents diffuse their conflict by involving the child. Note that during the third part of the interview, the parents’ free fatty acids rise steeply. Note also that when the child comes into the room, the parents’ free fatty acids fall while the child’s rise even more steeply. Part four is a turn off period in which the family relates alone in a room without interviewer, nurses, or two-way mirror being present.

Fig 1: Psychosomatically induced exacerbations of diabetes mellitus

If one assumes that free fatty acids correlate with stress, then the child can be seen as serving a function in the system. That is, in part four, he functions to relieve the stress that his parents were experiencing. However, the cost to the child is clearly demonstrated in terms of this rise of his free fatty acids and his ensuing symptomatology. In this sample, then, there is a clear demonstration of interrelationship between the child’s physiology and the extra-corporeal part of the child’s self.

Stemming from these divergent definitions of the self, there follows marked differences between the individual and family-oriented psychiatrists in the way psychosomatic children are conceptualized and treated. In the remainder of this paper, we will deal with a case of psychosomatic disease in a youngster. We will contrast how these two schools approach the areas of etiology, diagnosis, maintenance, and treatment, and the meaning of change.

Billy was three and a half when he was first referred to his allergist because of wheezing secondary to respiratory infections. At that time he had mild symptoms which, although severe enough to require a referral to a specialist, did not significantly impinge on Billy’s or his family’s daily life. The symptoms occurred sporadically over the next five years and until Billy was nine at which time his asthma became severe. He required numerous visits to emergency rooms and his daily functioning was impaired. His allergist reported a few allergies, namely ragweed and mold. Billy, a quiet youngster, was docile and passive especially when compared to his rough and tumble five-year-old brother, his only sibling. Billy was very close to his mother with whom he spend a great deal of time and confided many things.

An appraisal of the family situation revealed that Billy’s symptoms became severe at the time of the death of his paternal grandfather. At that time this father’s mother began spending more time with Billy’s father, her only child. At the same time, the father completed night school and was home more. The parents stated that this was something they had looked forward to for many years and were happy. Simultaneously, Mrs. K developed a handwashing compulsion which involved her asking her husband to verify that she had washed her hands. She even called him at work for reassurance. At the same time, Mr. K developed globus hystericus which exacerbated late each day at his job as an engineer. The symptom was only alleviated by having beer upon coming home, a practice his wife abhorred. On weekends, Mr. K, the younger son, and the paternal grandmother would go to the summer hone while Mrs. K stayed at home with Billy because his asthma was worse at the As seashore. As a result of her handwashing compulsion, Mrs. K was greatly limited in the amount of housework she could do. Her mother-in-law, however, rallied to her aid and even came over her day off from work to do cooking and housework. The other days of the week she was employed as a domestic.

At the time of psychiatric referral, Billy had a respiratory peak flow of 170 liters per minute with a normal of 220. His syndrome corresponded to Pinkerton’s Group IIA.[ref]P. Pinkerton, Correlating physiologic with psychodynamic data study and management of childhood asthma, J. Psychosomatic Res 11 (1967), 11-25.[/ref] His chest x-ray was essentially normal. He was on small doses of steroids and, in spite of this regimen, he continued to visit his local emergency room at least twice a month. The allergist* thought that the severity of his symptoms was in-consistent with his pulmonary function.

Dichotomies in the Concept of Diagnosis

The individually-oriented child psychiatrist examining Billy would note the following things: he is a dependent, very passive child who speaks only when spoken to, rarely initiates play, and looks quite sad. He only occasionally complains and even more rarely does he fully co-operate. When unhappy, he stoically tolerates his distress, complaining infrequently. From this vantage point, Billy has many of the psychological stigmatae which constitute a psychosomatic child. In evaluating Billy’s family the contextually-oriented child psychiatrist is guided by a model of a psychosomatic family which describes certain transactional patterns between family members. These patterns are a necessary conditions for the maintenance of psychosomatic symptomatology in families. There are five characteristics;

- Enmeshment describes inappropriately diffuse interpersonal boundaries between family members. Transactions are marked by intrusiveness with the net effect being an interference with the development and functioning of the members’ autonomy.

- Diffusion of conflict refers to the family’s inability to tolerate the expression of conflict within certain dyads. Instead conflict between members is avoided by involving a third person. A frequent pattern of avoidance is the focusing on the identified patient’s psychosomatic symptoms at moments of tension between family members, especially the parents.

- Overprotection is seen among family members and especially in relation to the psychosomatic child. Overprotection of a child is gauged against the backdrop of the child’s developmental level. The over-protection impairs the child’s acquisition of interpersonal skills.

- Rigidity of the family organization refers to stereotypical transactional patterns which are maintained even in the presence of pressures that require change for the optimal survival of the social unit. This inflexibility allows only a limited repertory of interpersonal responses when compared with non-psychosomatic families. Alternatives for adaptive behaviour in response to normal developmental crises are reduced.

- Participation of the identified patient in the conflicts of the family members. Frequently the child acts as a detourer of spouse conflict with the effect of maintaining the homeostasis of the parent’s marriage.

Billy’s family showed all of the characteristics of a psychosomatic family. There was an unusually high amount of conflict-avoidance which was most marked when differences arose between the parents. When this happened, Billy frequently became active and captured their attention so that the skirmish was soon forgotten although rarely resolved. Billy did this by manifesting a number of behaviors, from crying to talking, participating in the parents’ fight and even wheezing, all with the result of the parents riveting their attention to him. The effect on the family was the same – the conflict was avoided. In addition, mother was highly over-protective of Billy to the extent that she would let his younger brother go to the playroom, but requested that Billy stay in the room with her so she could keep an eye on him. The family’s enmeshment was manifested by disregard of the age-appropriate autonomy of it’s members. Furthermore, the members interacted in stereotyped ways to the extent that there appeared to be a limited number of permissible responses. Billy’s family would therefore be described as a rigid system. For the contextually oriented child psychiatrist to arrive at a diagnosis, then, of psychosomatic disease, it is necessary to look at all aspects of a field consisting of Billy, his family and their interrelationship.

Dichotomy Between Etiology and Maintenance of the Symptom

For the individually-oriented child psychiatrist, the asthmatic symptom is seen as the product of bio-psychological determinants manifesting themselves in the contractions of the bronchioli. Furthermore, the asthmatic child’s cry for help from the mother has been considered the underlying psychodynamic that accompanies the appearance of sibiliences in the asthmatic child. For the individually-oriented child psychiatrist, there is no distinction made between the etiology and the maintenance of the illness; the same psychological characteristics account for both. These characteristics are the result of the original learning experience and are called forth when the child is subjected to psychological stress.

For the family-oriented child psychiatrist, however, the factors responsible for the etiology and those determining the maintenance of the symptoms are separate. Similar to the individually-oriented practitioner, the family-oriented psychiatrist sees the etiology as historically determined with the child having a substrate predisposition toward the malady. The maintenance, on the other hand, is conceptualized as a result of the family organization. The family transactions function to bring to the fore-ground those aspects of the child’s self which result in the emergence of symptoms. By changing the particular ways in which family members interact and thereby organize each others behavior the family oriented child psychiatrist alleviates the psychosomatic symptom although the child maintains the same physiological predisposition toward the symptom.

As described above, Billy clearly had both the physiological and psychological predisposition to account for the etiology. To ascertain the transactional sequences which account for the maintenance of his symptoms the child psychiatrist scanned the family’s transactions. He noted that Billy’s family was overprotective. For example, Mrs. K insisted on being home for lunch on school days even though she wanted to be working instead. Furthermore, the children preferred to stay at school. The fact that were not allowed to make this decision is an example of the enmeshment that was ubiquitous. Conflict avoidance with participation of the third parties, especially Billy, was the rule. Recurring in the family transactions was a type of participation in parental conflicts, triangulation, in which Billy was inextricably caught in the parental conflict. For example, Billy’s father said, “Billy, do you think I spend too little time with you or that mother spends too much time with you?”

The dichotomy between the individually oriented psychiatrist’s emphasis on etiology and the family-oriented practitioner’s emphasis on maintenance is an important pragmatic difference in the psychiatric management of psychosomatic illnesses.

Concepts of Onset

The individually-oriented child psychiatrist would probably see the onset of Billy’s asthma as related to the death of his grandfather since the two events are chronologically contiguous. It would be assumed that Billy, who had a close relationship with his grandfather, deeply felt the man’s loss. His ensuing loneliness, as well as a decrease in the amount of emotional support, put him at a significantly greater risk for manifesting symptoms. Onset of symptoms, then, for the individually-oriented psychiatrist, would be seen as related to events which translate into greater stress for the identified patient.

For the family-oriented psychiatrist, onset is similarly related to the death of the grandfather since the chronological association is evident. The significant difference, however, between the two schools is in how the event of the grandfather’s death leads to the onset of symptoms. The death is seen, by the family-oriented therapist, in terms of the effect not solely on Billy, but on the entire family. The death of the grandfather resulted in Grandmother, who was depressed, needing increased proximity to her son, Billy’s father. Father responded by spending much more time with his mother. This caused his wife to experience a loss and an emptiness in her life. She compensated by getting closer to Billy, who became isolated from his peer group, resulting in an increase in adult social skills and a relative developmental deficit of peer-appropriate social skills. Billy then spent more time around the house where he was more likely to become involved in the transactional sequence that results in the maintenance of his symptom. Of course, the fact that father was much less available to mother and closer to his own mother only served to increase the conflict between the spouses. This functioned to add instability to their relationship increasing the need for the sequence described above in which Billy participates in the transactions between the parents in such a way that they avoid conflict. This sequence becomes more common the greater Billy’s availability and the more unstable the parent’s relationship.

We may speculate, at this point, about the way family organisation influences symptom selection. Billy’s parents, both of whom were extremely active in amateur singing groups, placed a high value on respiratory functions and especially breath control. When Billy, then, had his first manifestation of breathing difficulties, his parents, as a result of their concern with breathing, focused in on his difficulty. Their focusing served to dissipate any conflict between them at the moment. Both the attention and the decreased tension between the parents functioned to reinforce the wheezing. Following this event, the parents became even more attentive to Billy’s breathing, and responded even more readily to any respiratory difficulties Billy might have.

Even more significantly, the K family is one with a predisposition towards somatisation. Mr. K has his globus hystericus, Billy his asthma, and Mrs. K her handwashing. This last symptom may be construed as a somatic symptom to the extent that her emphasis is on one of her body parts, that is, her hands, and, more specifically, she is obsessed with a defect – her “dirty” hands. All three family members, therefore, manifest a tendency toward obsessive rumination about their bodies. To summarize, when Billy, then age three and a half, began to manifest some respiratory family focused on these. Even though the initial precipitating cause may well have been some exogenous allergin, the family’s focusing on this somatic symptom which fit into their own pattern of somatization tended to reinforce the symptom. The symptom was then more or less quiescent until the grandfather’s death which greatly disequilibriated the family system. There were then frequent exacerbations of the symptom. These can be attributed to the increased tension in the family and the family’s pattern of conflict-avoidance and the participation of the children to help diffuse the conflict, both of which as noted above, are characteristics of the psychosomatic families.

Dichotomies in Concepts of Change

Inherent in the approach of the family-oriented psychiatrist is a conceptualization of change that is widely divergent from that of the individually-oriented child psychiatrist. In the latter, change in a child is related to the etiology of the process. Therefore, the patient will need to overcome his own history and psychological patterns that were determined in early relationships between the child and significant others. In this sense, the concept of change is tied to over-coming internalized pathology.

The family-oriented child psychiatrist separates the concepts of etiology and symptom maintenance; therefore, his conceptualization of change deals with the transformation of the social system that maintains the symptom. Within this orientation, the therapist can help family members to find alternative ways of relating so as to change the feedback system in which the symptomatic child is imbedded. The “self”, which in the family model includes the feedback system, will therefore be changed since the transactions with a child’s significant others has been altered. Change includes not only the exploration of the pathology of the dysfunctional determinants of the symptoms but, even more importantly, it includes the exploration and development of new capacities of coping by the child and the family. These new coping capacities are initiated not only in the identified patient, significant individuals who form the feedback mechanisms which help to define which complement and thereby shape the identified patient. Once the therapist has joined with the family to create the therapeutic system, the therapist also becomes a feedback-giving individual who helps to shape and call forth aspects of the patient’s personality. This therapeutic involvement is another major difference between approaches in family-oriented child psychiatry, since the therapist is seen as part of the child’s extra-corporeal self.

Different Approaches to Treatment

The question of treatment brings up another important difference. The individually-oriented child psychiatrist assumes that the psychosomatic syndrome is the product of unresolved internalized psychological conflicts. By reason of this point of view, the therapy is directed at the understanding and working through of early experiences so that the child responds more adaptively to stress.

Since the family-oriented therapist conceptualizes the dysfunctional sequence as circular, he can intervene at any point and affect the other parts. For example, he could send Billy to Denver thereby rendering the youngster unavailable to the family for maintenance of the homeostasis. This is likely to be effective although Billy’s brother might become symptomatic in some way, for example, developing headaches, and thereby occupy his brother’s role in the dysfunctional sequence (symptom substitution!). Furthermore, whether or not this happens, Billy, on returning home to the family may very well return to the dysfunctional interactional pattern that had maintained his symptoms. On the other hand, the youngster might have matured and acquired sufficient skills while away to be able to remain aloof from the dysfunctional sequence. Parentectomy, nonetheless, is indirect, costly, and not without iatrogenic complications.

The contextually oriented child psychiatrist’s treatment of Billy’s family is best described in terms of creating boundaries around subsystems: around the parents’ marriage, grandmother with her generation and Billy with his brother and peers.

Strengthening the boundary around the parents’ relationship was accomplished both inside and outside of therapy sessions. In the session, the therapist helped the parents enact transactions in which they resolved differences without involving a third person. These effective dynamic interactions served as templates for family transactions at home. The spouses were encouraged to explore common interests, which led to them spending more time together on weekends. They were helped to normalize their life in spite of their child’s problems.

The therapist worked closely with Billy to help the youngster take more responsibility for his asthma. This not only enhanced Billy’s self-confidence but it made him more independent, allowing the parents more space to develop their relationship.

The psychiatrist helped Father in his intense commitment to rescue his own mother from her depression. Re worked with the family to involve the older woman in various community groups, with friends, distant relatives and with new found interests; thus helping her to adjust to widowhood and allowing her son more time to focus on his wife and family.

Therapy was also directed at strengthening the sibling subsystem to help the brothers to support one another’s involvement in parental conflicts as well as to create norms for age-appropriate social skills. Billy’s involvement with peers was encouraged by the therapist.

In the process of achieving these goals the therapist dealth with the rigidity of the family system and the stiffling overinvolvment between family members – two dysfunctional patterns that impeded the members’ development of creative responses and individual autonomy.

The therapist in this case followed these treatment goals with an amelioration of Billy’s asthma occurring within a month. Being less symptomatic, Billy no longer required unscheduled visits to his doctor or the emergency room. He was able to function more normally with peers. He and his brother had more fun together although they fought more.

A two and a half year follow-up revealed that Billy occasionally had mild episodes of shortness of breath but had no frank wheezing. The parents reported that the youngster was more independent and assertive; they complained that for the first time they had to punish him occasionally. He had more friendships and was doing well in school.

The parents’ symptoms no longer disrupted their lives. Mrs K stated that although she frequently had the desire to wash her hands, she was able to control the wish. Similarly, Mr. K’s globus hystericus had diminished to the point that he no longer had to have a beer upon coming home from work. But, since their marriage had improved and he and his wife had resolved their dispute over his drinking, he now frequently had a beer because he wanted to even though he no longer had to have one. Grandmother was reported to be very busy and better adjusted to widowhood.

Conclusion

What does this case tell us about the theories discussed in the first part of paper? First of all, there was not one patient, but four: Billy, with his asthma; mother and her handwashing compulsion; father with his globus hystericus; and grandmother with her existential depression. The therapist approached the problems not by focusing on a particular individual and his/her symptom, but by understanding and then altering the way family members interacted and affected each other. And the treatment was measurably effective because these symptoms were alleviated. Thus, through weekly treatment lasting six months, the necessary change was effected and the family members were free to move on; the treatment was economical from a psychological and financial point of view.

But does this family’s therapy substantiate the concept of extra-corporeal ‘self’ that Bateson posited in his metaphor of the blind man? Of course no anecdote can prove the effectiveness of a therapeutic approach or a scientific paradigm. A study,[ref]B. L. Rosman, S. Minuchin, R. Liebman, L. Baker, Input and outcomes of family therapy in anorexia nervosa, Successful Psychotherapy, ed. J. Claghorn. Brunner/Mazel, 1976. Chapter VIII.[/ref] however, of a large treatment sample of psychosomatic children and their families with a subsequent follow-up of two to nine years bears out what this example demonstrated: that an expanded concept of the ‘self’, which underlies the contextual approach, is useful in understanding and treating psychosomatic children.

END